In an apology letter sent to the PETA Foundation, an official with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) claimed that a “miscommunication” led NIH security guards to prevent PETA Vice President Dr. Alka Chandna from speaking at a public meeting on the agency’s main campus in February—in apparent violation of her First Amendment rights. Dr. Chandna is pleased to have received a mea culpa from NIH over its alleged viewpoint discrimination, and she looks forward to future public meetings, at which she can advocate for animals who are locked in laboratory cages and subjected to painful, terrifying experiments. But PETA wants to communicate our position clearly: If NIH is issuing apologies to those it has wronged, it owes a big “I’m sorry” to the millions of animals who have suffered in the pointless experiments it funds.

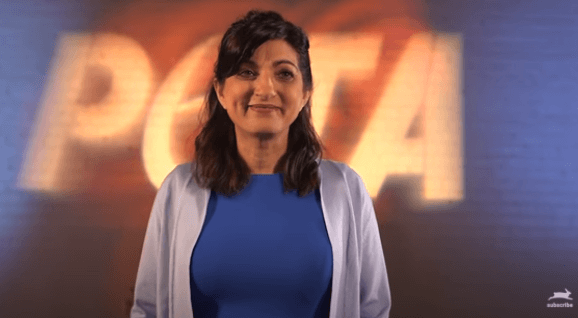

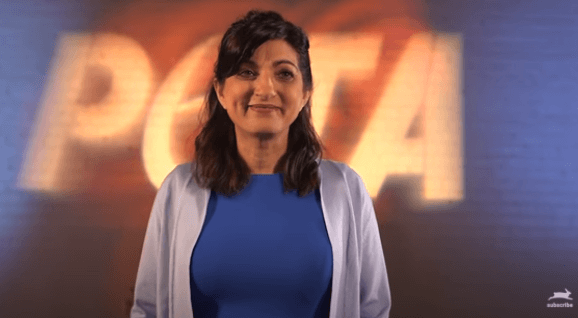

“PETA and I are determined to push NIH toward an animal-free future of sophisticated, human-relevant research methods.”

—Dr. Alka Chandna, Vice President, PETA

The apology from NIH came only after PETA threatened legal action over the agency’s unconstitutional actions in February, when, despite receiving an invitation from NIH to speak at an on-campus public meeting of the National Advisory Mental Health Council, Dr. Chandna was told by NIH security personnel that she had been banned from the agency’s campus.

Their excuse at the time? A couple of months earlier, Dr. Chandna had exercised her right to free speech by posting flyers in public spaces on NIH’s campus that were critical of the agency and urged it to end its worthless monkey fright experiments.

By banning Dr. Chandna from its campus because of her viewpoint and her affiliation with an organization that advocates for the ethical treatment of animals, NIH blatantly flouted free speech protections guaranteed by the First Amendment.

We’re pleased that, with its apology, the agency provided assurance that Dr. Chandna won’t be unconstitutionally excluded from its campus.

NIH experimenter Elisabeth Murray carves out sections of the skulls of monkeys used in her experiments, and then injects toxins into the animals’ brains, or suctions out parts of them, causing permanent and traumatic damage. The monkeys are then put all alone in a small metal cage, which is contained inside a larger box painted black. A guillotine-like door at the front of the cage is suddenly raised, revealing a fake but realistic-looking snake or spider to frighten the monkeys.

Some monkeys respond defensively—freezing up or looking or turning away. Others shake their cage. Some grimace or smack their lips—signs of submission in the face of a threat. The monkeys endure this same torture repeatedly, until they are eventually killed or recycled into other experiments, to be further tormented.

NIH claims that these experiments shed light on human neuropsychiatric disorders, but not one treatment or cure for humans has come out of them in more than 30 years.

The agency may not want Dr. Chandna or PETA to criticize the failure of its experiments on monkeys, but that doesn’t mean it has the right to silence us in public forums.