These comments, while typical of young children, can stop a teacher in her tracks. How should teachers respond? Children’s comments can sometimes fluster both new and experienced teachers—even those who support equity and diversity in schools. While teaching at the Eliot-Pearson Children’s School at Tufts University, this article’s authors explored what it means to embrace an anti-bias stance every day. They found that adopting an anti-bias perspective requires more than implementing a few well-meaning activities. Instead, doing so asks educators to think differently about their work, take personal and professional risks, and put new ideas and beliefs into practice. The teachers at Eliot-Pearson developed a framework to guide their anti-bias work and support their anti-bias planning and practice as they moved forward (Kuh et al. 2011).

Anti-bias education is a way of teaching that supports children and their families as they develop a sense of identity in a diverse society. It helps children learn to be proud of themselves and their families, respect a range of human differences, recognize unfairness and bias, and speak up for the rights of others (Derman-Sparks & Edwards 2010). Children tell us every day via their comments, play, and peer interactions that they notice social issues, are curious about differences, and want more information. So what do schools and teachers need to do?

In many ways, anti-bias education may not be so different from the kind of teaching that educators already do. For example, when children notice butterflies in the garden, teachers might notice and respond to children’s curiosity as an opportunity for extending curriculum, and then provide books and other materials about life cycles. But when it comes to talking about race, class, gender, family structure, or ability, teachers might consciously, or even unconsciously, avoid elaborating on these topics.

Anti-bias curriculum topics often come from the children, families, and teachers, as well as from historical or current events. Anti-bias education happens in both planned curriculum and natural teachable moments based on children’s conversations and play. Teachers have to balance planned anti-bias teaching experiences, such as mixing paint to match skin color, with seizing emergent opportunities to engage children by responding to their questions and observations. This can be challenging, and requires the ability to see anti-bias work as an opportunity to teach (as opposed to overcoming a problem). Embracing an anti-bias stance helps teachers to develop innovative practices tailored to the populations they serve. It might be difficult to know where to start, and there is not always an easy answer. It is important for teachers to find a balance between addressing children’s needs and not upsetting families, and at the same time to take a stand that may be socially or politically charged. Does all this belong in the early education setting? Is it part of teaching?

The Eliot-Pearson Children’s School’s long-standing commitment to anti-bias education is part of its core values and mission. However, being intentional about anti-bias education across classrooms wasn’t always easy. One year, as a curriculum strategy, each classroom focused on a particular issue related to its group of children. The teachers shared documentation and questions about this focus at monthly professional development meetings, getting and giving feedback on curriculum and teaching practices. Topics included same-sex parents, skin color and racial identity, class and power, abilities and challenges, and cultural backgrounds.

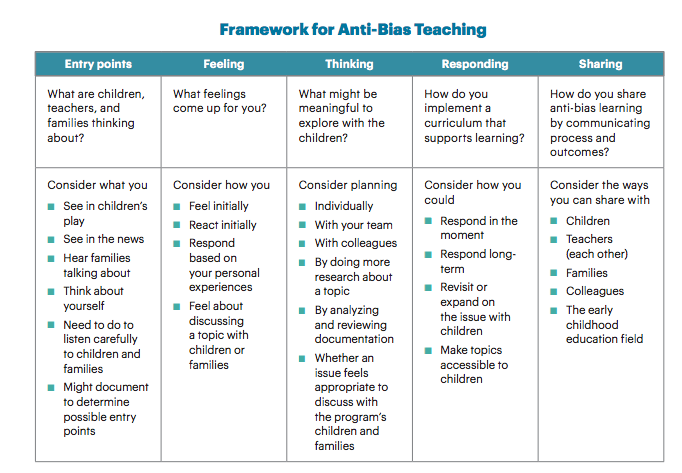

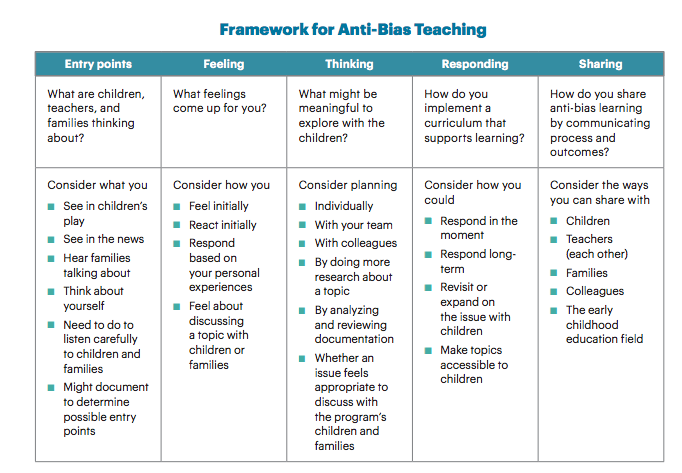

To hold themselves accountable for anti-bias work, the program’s teachers developed a tool for keeping anti-bias issues alive in the curriculum (see “Framework for Anti-Bias Teaching,” p. 59). The work of three of this article’s coauthors—Lisa (pre-K), Heidi (kindergarten), and Margaret (mixed-age first and second grade)—illustrates curriculum development prompted by the framework and support for anti-bias work for individual teachers and for the school as a whole. The framework has been modified further and discussed in more detail in Leading Anti-Bias Early Childhood Programs: A Guide for Change (Derman-Sparks, LeeKeenan, & Nimmo 2015).

Entry points include identifying, provoking, or uncovering themes children are thinking about or demonstrating in their play. An entry point may be something a family brings to a teacher’s attention or something a teacher knows about a family that a child brings to the setting. It may be a topic in the media—such as an election, a demonstration, or a film—that draws attention to a particular issue. In addition to recognizing entry points educators should understand that their responses to children’s queries don’t have to be instantaneous. They may not know right away how to respond—or whether they even want to explore a particular issue with a group—but the awareness of the topic is an important first step. Identification of entry points is at the beginning of the road map for curriculum planning. It takes place with the understanding that anti-bias issues raised are not problems to be eliminated, but rather opportunities for teaching and learning.

Margaret’s First- and Second-Grade ClassIn this mixed-age inclusive class, teachers hear children saying things like “That’s not fair! She gets an easier sheet than me!,” “Why does he get to use a rocking chair at meeting? Can I?,” and “I am bad at reading.” Margaret knows that children’s notions of fairness and their perceptions of themselves and others as learners provide entry points to rich conversations. Ability differences and similarities are part of a conversation that starts on the very first day of school.

Heidi’s Kindergarten ClassWhen Heidi hears kindergartners say, “This is my ramp. This is a private ramp,” and “You can go up any ramp, if you have a lot of money. People with a lot of money can go in anywhere they want,” she realizes that children are thinking about issues of ownership, resources, and power. This “a-ha” moment inspires her to pay close attention to the language and understandings children have about social class, wealth, and privilege. As the kindergartners play, she notes that the children’s attempts to assert themselves often reference possession (“I got it first”), ownership (“That’s mine”), status (“I am the boss”), and cultural capital (“If you don’t know this movie, then you don’t know how to play”).

Lisa’s Pre-K ClassFor sharing time, 4-year-old Julian, who is biracial, shows photographs of an experiment he did at home in which he added cream to his mother’s coffee to try to match the color of his own skin. Later, 4-year-old Tywanna tells her lunch tablemates, “I’m lucky because my mom is light and my dad is dark and I am in the middle—a mix!” Hearing this, Lisa and her teaching team realize that children are grappling with racial identity. The teachers decide to work with the class to help children learn language to talk about race together.

For each potential entry point, it is important for educators to identify their feelings related to the anti-bias issue. Teachers may not necessarily know who to talk to about their feelings, and often this is where they get stuck. Their personal experiences may drive their responses, or they may experience discomfort and ignore the topic altogether. For example, Heidi felt overwhelmed and dismayed at the play she observed, based on her own class background. Teachers often change the subject when anti-bias topics come up or redirect children to distract them from the topic at hand. At Eliot-Pearson, the framework helps teachers address ambivalent feelings they have about a topic. Discussing their feelings about a topic with colleagues can help educators gain clarity about how to manage the curriculum.

Margaret’s First- and Second-Grade ClassMargaret is upset that the children in her classroom are using ability to gain social power. It bothers her that differentiating curriculum based on children’s skill levels seems to be provoking competition between students, sometimes hindering their self-confidence and willingness to take academic risks. Margaret worries that by exploring and discussing abilities, children will feel singled out by their differences. Would asking students to admit that they are challenged by some assignments be comfortable or productive? Would a particular child with obvious physical differences be able to participate in the conversation, or would classmates see him as a mascot for inclusion rather than an equal member of the class?

Heidi’s Kindergarten ClassHeidi struggles with the connections she sees between kindergartners’ play and issues of access, possession, and power present in our society. While she feels excited and nervous as the children explore social class concepts, she also worries about approaching a subject that seems taboo even in adult conversation. As she explores her own feelings, she wonders, “What role do teachers play that might be supporting and reinforcing ideas of ownership as power? How do our own class backgrounds affect perceptions of children, and how might our backgrounds equip us, or not, to support the children as they expand their understanding of these ideas?”

For each potential entry point, it is important for educators to identify their feelings related to the antibias issue.

Once the teachers at Eliot-Pearson considered entry points that identified areas of interest to the children and acknowledged their own feelings, they got down to the business of thinking about potential next steps. Documentation is crucial in inspiring teachers’ thinking. The documentation process involves raising questions and closely documenting children’s experiences. Teachers can take photographs, listen to and record conversations, and observe and videotape children’s play. They can continue to bring questions to colleagues, using the documentation to ask questions such as “What are these children working on and why?” and “What can I do in my classroom to support children’s exploration and understanding of this topic?”

Initially, the kindergarten teaching team was stuck—unsure about how to explore ideas of possession and power with children this young. Teachers shared their thinking with families and colleagues, learning about the values they thought were important. Teachers began to look at power as a way to consider acts of sharing and giving (rather than having and holding)—encouraging the children to “use their powers for good.” They developed activities that asked children to think about times when they had used possession or ownership to assert power, and to generate possible solutions to fairly distributing and using classroom resources and materials

Lisa’s Pre-K ClassLisa and the pre-K teaching team review Julian’s coffee photographs and, with his parents’ knowledge and permission, talk with him further to explore the motivation behind his experiment. He says that he is mulatto (a term that refers to someone of mixed race), but because that term has fallen out of favor in the United States, some teachers feel uncomfortable hearing and using it. Teachers begin keeping track of children’s conversations about race and skin color at play, lunch, meeting, and outdoors. Children’s comments reveal confusion about what White and Black really mean in relation to skin color. They point to each other’s clothing, noting that someone has white pants or a black shirt. As a result, the teachers think about ways to broaden and clarify skin color vocabulary before starting any skin color paint mixing.

Much of the work up until this phase involved observing, reflecting, documenting, and questioning. In the responding phase, teachers plan and implement intentional, specific experiences. Teachers choose curriculum changes to implement in the moment and through long-term planning. Again, documentation plays a part, as analysis of children’s conversations can help teachers choose what to respond to and how to respond. Teachers also offer children the skills and tools they need for specific learning experiences. In the butterfly example (from the opening page), teachers might give children opportunities to explore with magnifying glasses and clipboards before heading out into the garden. Providing children with initial materials and experiences can support their later engagement with deeper content. With anti-bias curriculum, these guided experiences might occur by simply mixing various colors of paint before beginning to explore skin colors.

Margaret’s First- and Second-Grade ClassOver the course of two months, Margaret invites visitors into the mixed-age classroom to teach and share information about many kinds of ability differences. They discuss a range of ability differences, including physical, sensory, social, emotional, communication, and cognitive. An assistive technology teacher shows the students how some children who are developing expressive language skills use computers to help them communicate their ideas. A local university student tells the children about her own reading challenges and shares a strategy she uses for tracking words on a page. A former student with vision impairment engages the children using humor by animating his voice as he tells a story. Margaret and the children create a classroom book documenting these conversations with visitors. As they revisit the book, they reflect on the idea that everyone has things they are great at and things they are working on. The children ultimately include pages about their own abilities and challenges. One child writes, “I am great at math problems. One thing that is challenging is waiting and raising my hand.”

Heidi’s Kindergarten ClassDuring a planning session, the kindergarten teachers identify three phrases that are commonly used during the children’s negotiation of play: “But I got that first. It’s mine,” “I have the [toy], so I have to be the boss,” and “We should have a rule that the person who has a thing decides the rules for the thing.” Heidi talks to the children about these phrases. Children and teachers spend two meetings telling stories about times when these phrases were used to assert power over others. Heidi then presents a provocation: “Should we use the words we talked about at meeting when we use the bikes?” The children immediately chorus, “No, no. Those rules are no good. They’re not fair.” Over the next three weeks, kindergartners debate and develop a plan for sharing the bikes and wagons, which includes having a sign-up sheet for sharing vehicles and considering the needs of preschoolers, who are often passengers.

Lisa’s Pre-K ClassLisa and the preschool team (two White teachers and one Black teacher) spend weeks engaging with the children in sensory- and art-inspired paint-mixing activities. In doing so, the children move beyond the novelty of color mixing to focus on systematically producing a color close to their own skin. Children name their various skin color shades—bologna being the most notable! Children also dramatize the Rosa Parks story to talk about White and Black as terms attributed to whole groups of people who really aren’t that exact color, and they discuss the exclusionary practices associated with those terms.

Sharing: Process and outcomes

Teachers at the Eliot-Pearson Children’s School regularly use documentation to make learning visible to children, families, and school visitors (Rinaldi 2006). Teachers wanted to share what was happening with the anti-bias work and created documentation to show the scope and depth of the children’s learning. The school year culminated in an anti-bias exhibition and gallery walk that was open to the public. Each classroom team made a documentation board that illustrated the different sections of the framework and shared key outcomes of the children’s experiences. Visitors could share questions and comments and add their own ideas by responding to several interactive bulletin boards through writing messages on sticky notes.

Margaret’s First- and Second-Grade ClassHaving documented classroom learning and shared the anti-bias work with families and school visitors, Margaret and her team now feel more comfortable discussing abilities and addressing unfair language in the classroom. Margaret notes the increase in children’s use of the phrases “what he’s [or she’s] working on” and “just right” work to explain why different children have different assignments. Children share their diverse abilities with each other by writing comments on sticky notes in response to each other’s pages in the classroom book. Margaret notes how children are able to take more academic risks and how she differentiates tasks in heterogeneous skill groups more flexibly, often referencing the classroom book when differences arise.

Heidi’s Kindergarten ClassThe long-term planning time and subsequent use of the sign-up sheet enable kindergartners to plan for using classroom and school resources and to express and negotiate roles, story lines, and connections rather than arguing over who gets a turn and who gets to control the play. Teachers experiment with different ways to dismiss children at choice times, so that no one “got there first.” Teachers’ efforts to change some classroom structures, in tandem with the plans made for sharing bikes, support teamwork and problem solving in play.

Lisa’s Pre-K ClassThe preschoolers share their learning by inviting families or children’s caregivers who have come to school to mix paint to match their own skin colors. With the children as expert color mixers, the classroom visitors create their skin color, experiencing the expanded vocabulary about race that the children developed. On their gallery walk panel, Lisa presents information from research about race so families can see how it connects to the work in the classroom.

It is important to note that throughout this exploration of anti-bias topics, the teachers at the Eliot-Pearson Children’s School had some key structures in place that were vital to their ability to sustain the hard work of reflective teaching, especially as related to potentially controversial topics. The following structures were included:

Working through the movements of the framework can bring up feelings of discomfort and move teachers to question which topics are introduced and how they are covered in their teaching practices. One teacher admitted, “It is still so hard to set priorities and decide what aspects of all the potential discussions get my attention, air time, group time, and curricular development.” But teachers were adamant that the work was worth the effort. Another teacher expressed it this way: “I am a learner too. Curriculum should be about actively exploring a topic with each other. I learned that part of our job as teachers is to aid children and families in areas they may be struggling with. Though our ideas and beliefs may differ, it is still our job to negotiate through these.”

Doing this work was not always easy, but it was rich, it shifted practice, and ultimately it was satisfying. Observing children as they have their own “a-ha!” moments—noticing an injustice, developing a new connection to a peer, or building an understanding of the world around them and their own role in making the world a more just place—is inspiring. It is equally satisfying to teachers to have taken a risk and stretched our own learning as a means to provide a deeper and more inclusive education for all.

Derman-Sparks, L., & J.O. Edwards. 2010. Anti-Bias Education for Young Children and Ourselves. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Kuh, L.P., D. LeeKeenan, H. Given, & M.R. Beneke. 2011. “Framework for Anti-Bias Teaching.” Unpublished curriculum tool. Medford, MA: Eliot-Pearson Children’s School, Tufts University.

Rinaldi, C. 2006. In Dialogue With Reggio Emilia: Listening, Researching, and Learning. Contesting Early Childhood series. New York: Rutledge. School Reform Initiative. 2012. Protocols. www.schoolreforminitiative.org.

Photos: 1, © iStock; 2, courtesy of the authors